Yet, as I noted in my June 23 post, the Greeks faced two horrible choices; default and eventual "Grexit" from the Eurozone, or additional austerity that would likely solidify Greece's position as an economic basket-case well into the foreseeable future. It seems that the closure of Greece's banks and the imposition of capital controls concentrated a lot of minds by giving Greeks a bit of a preview of the acute pain a "Grexit" might bring about. However, opinion remains divided (including, evidently, within Mr. Tsipras' governing coalition) over whether the best option for Greece might in fact be a "Grexit." But which path is actually worse? Grexit or austerity? The answer isn't so simple.

Yet, as I noted in my June 23 post, the Greeks faced two horrible choices; default and eventual "Grexit" from the Eurozone, or additional austerity that would likely solidify Greece's position as an economic basket-case well into the foreseeable future. It seems that the closure of Greece's banks and the imposition of capital controls concentrated a lot of minds by giving Greeks a bit of a preview of the acute pain a "Grexit" might bring about. However, opinion remains divided (including, evidently, within Mr. Tsipras' governing coalition) over whether the best option for Greece might in fact be a "Grexit." But which path is actually worse? Grexit or austerity? The answer isn't so simple.There are a lot of villains and victims in this Greek tragedy, some of which are detailed in and excellent New Yorker piece from March of this year.We know what austerity looks like in Greece; 25% unemployment, a depression-like emergency atmosphere, and little prospect of Greece actually growing its way out of it's economic hole. Greece's banks have reopened, but "normal" is likely going to need a serious re-definition for most Greeks in the years ahead. The consequences of austerity are so objectionable that others, such as the Wonkblog's Matt O'Brien, argue that default and "Grexit" might offer a less painful path forward. But would it?

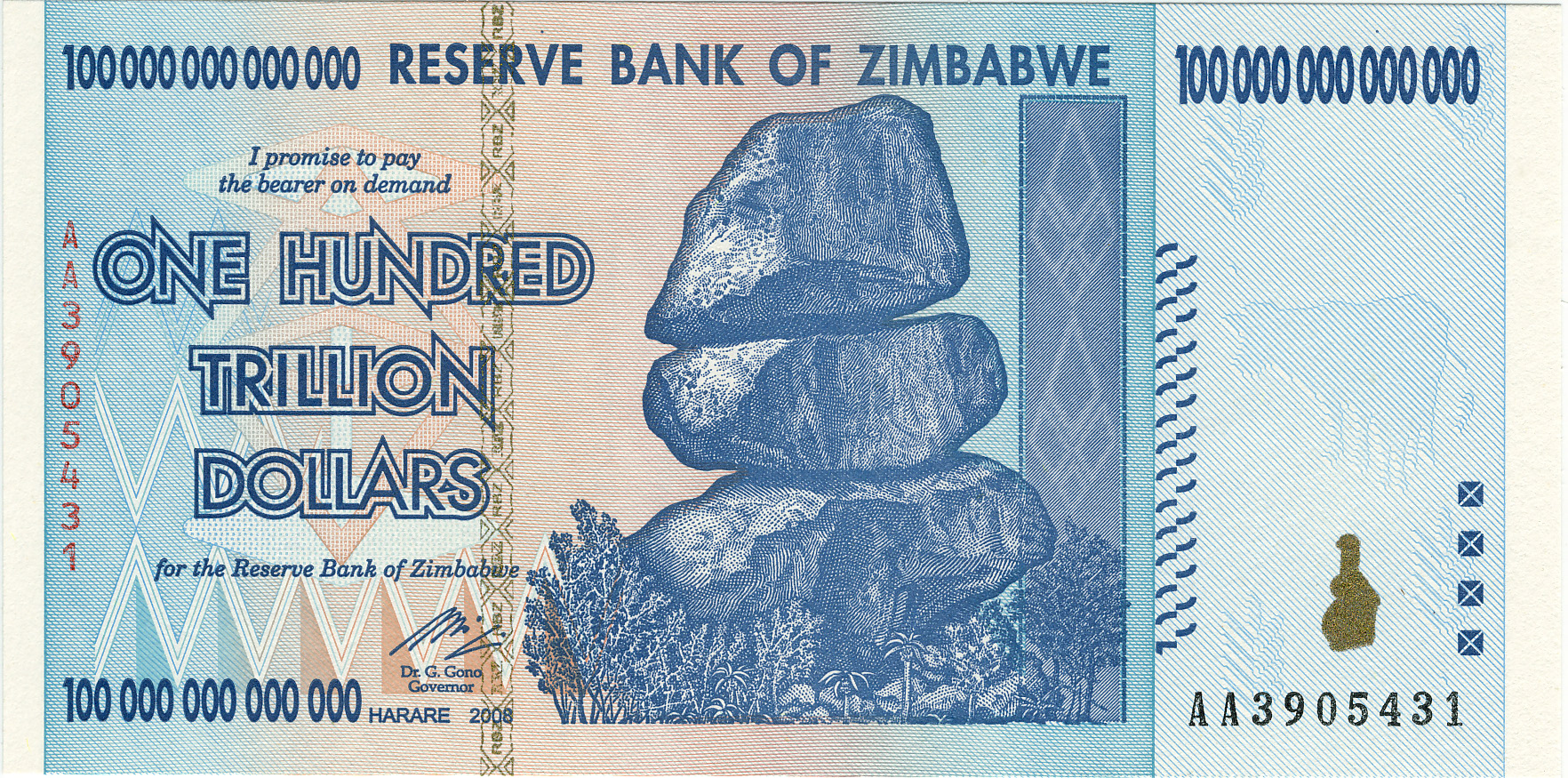

Matt O'Brien's piece about the restrictiveness of Finland's membership in the Eurozone makes some compelling arguments-- some of which I touched on in my late June post. Any regime of fixed exchange rates or, in the case of the Eurozone, the even more restrictive monetary union we see in the Eurozone, entails a number of highly restrictive policy trade-offs. First and foremost, participation in any such regimes entails the ceding of your monetary sovereignty. This is no small matter. Monetary policy is one of two major policy domains available to governments to shape domestic economic activity; the other being fiscal policy. Pooling your monetary sovereignty with others via political arrangement or within an institution (such as the ECB) is not inherently bad; you eliminate exchange uncertainty, get access to cheaper capital by bundling credibility, and smooth wages and efficiencies throughout member states, and significantly limit the threat of inflation (a major reason countries typically adopt fixed regimes). The flip-side here is that you no longer have monetary policy tools at your disposal (interest rate setting and money supply) to influence economic activity. Yet, if your (mis)management of monetary policy has repeatedly netted high rates of inflation, the limitations of ceding monetary policy to some other authority might be worth the cost (see Zimbabwe below).

This it is a tricky situation for individual economies since the centralized monetary authority engages in policy making that is broader than any single member state. Interestingly, one of the strong recommendations from the IMF flowing from the financial crises in East Asia in the late 1990s was that you shouldn't fix your exchange rates. External shocks or fiscal debt burdens that become too high can quickly destabilize such regimes.

The Argentine Model?

Well, perhaps. In 1992, Argentina adopted a form of fixed exchange rate regime in which the peso was fixed to the value of the US dollar. Along with the fix came tremendous credibility in monetary affairs, including access to US dollar denominated lending at low interest rates. But then things began to go awry (external shocks) when Brazil, one of Argentina's most important trading partners, experienced its own financial panic in 1998. Argentina began earning less and less from exports that foreigners, especially Brazilians, found expensive. Argentina began to bleed cash as it continued to pay for imports with reserves that were not being replenished by export earnings. Default on Argentine debt and an inability to fund basic government services came in late 2001 when Argentina set the record for the largest ever sovereign default, $155billion.

In January 2002, Argentina went off its fixed regime and allowed the peso to fall in value (devaluation). For a short while, Argentina's economy looked much more competitive; its beef and wine were less expensive, and it was cheap to vacation there. More importantly, Argentina began accumulating export earnings. As O'Brien and others note, the same effects could begin the turn-around in Greece. Greece under the Euro is a very competitive economy at the moment. If the drachma was re-introduced, what ever Greeks produced (really only olive oil, as far as I can tell) would be cheaper for foreigners to buy and, more importantly, it would be much cheaper for you and I to visit the Acropolis.

Some commentators have argued that Argentina should be considered something of a model for dealing with international creditors and un-payable debt. Yet, Argentina hasn't exactly been the poster-child for economic growth and stability since 2002. As soon as the peso was de-linked to the US dollar, its value dropped like a rock. It restored some competitiveness for Argentina's export sector (beef, wine, tourism) that served as a source of foreign reserves. Yet, as the value of the peso fell, everything Argentina imported from abroad became very expensive. The country's credibility with international creditors collapsed with the abandoning of the fixed exchange rate-- one of the main reasons for adopting the fix in the first place. More importantly, Argentina had accumulated huge sums of debt denominated in US dollars while the peso was fixed. Once Argentina abandoned the fix, it faced the daunting task of having to pay off those loans with a falling peso. Moreover, their credibility in monetary affairs shot, Argentina couldn't raise additional capital from abroad to meet those obligations.

While some sectors of the Argentine economy have enjoyed renewed competitiveness, the crisis has been unambiguously devastating for many others. Crisis management, including non-stop legal battles with creditors, has become the norm. Compounding these problems, Argentina defaulted on its debt yet again in July 2014, further eroding any ability tap international credit markets at reasonable interest rates-- what creditor wants to lend to a country that may or may not pay them back?

Default and Devaluation?

Some commentators have speculated that an "orderly Grexit" could be engineered to shield everyone (Greece, other Eurozone members, and the global economy) from some of the long-term chaos that has affected Argentina. But it would be tricky. No provisions for exit from the Eurozone have ever been contemplated. Moreover, countries that have tried to revamp, transform, or reintroduce currencies after a financial melt-down have not been especially successful; Zimbabwe may be the poster-child for such mismanagement.

In 2008, Zimbabwe embarked on an extreme experiment in monetary management by adopting the US dollar. Ecuador and El Salvador have also had recent experiences with dollarization.

Greece confronts some of the same problems Argentina did in the early 2000s; a fixed exchange rate an unsustainable debt burden, and an uncompetitive economy. Greece should arguably never have been admitted to the Eurozone in the first place. Indeed, there have been plenty of accusations that Greece lied about its financial health in order to secure membership. However, once inside the Eurozone, Greece drafted considerable credibility for itself by tying its monetary affairs to the ECB. This is most notable where Greek inflation rates are concerned, which prior to joining the Euro, were stubbornly high, often well over 20%.

After a "Grexit," a new drachma would, much like a post-fix Argentine peso, quickly fall in value. Greek export competitiveness would return, but imports would be expensive, and Greek debts, many of which have been denominated in Euros, would have to be paid back in terms of drachmas that, for a while at least, would be worth very little. In the transition, Greece would probably impose even tighter capital controls to prevent the flight of capital out as investors tried to get out before their investments were re-denominated in falling drachmas. Moreover, access to foreign sources of capital would be both limited and expensive for virtually all sectors of the Greek economy (private and public). There might be bargains to be had in Greece, but the risk premium on any sort of investment in Greece might be prohibitively high in the wake of a "Grexit" to the drachma.

To avoid some of this, Greece would have to adopt the kind of sound management of its newly-sovereign monetary policy that, until now, it hasn't shown in many other areas of its economy. While control over your monetary affairs sounds good, it comes with its own set of risks, including the all-too-frequent tendency for governments to turn on the currency printing press in an effort to inflate away many of the debts owed to Greeks themselves. This of course leads to the evisceration of wages, purchasing power, and eventually bouts of hyper-inflation.

Devaluation vs. Float

Some may see semantic quibbling in the distinction between devaluation and letting your currency float, but it's critically important politically. It's one thing to abandon a fixed exchange rate and allow your currency to "float" in response to international supply and demand signals (note the slide in the Canadian dollar vs. the US dollar) . It's another matter entirely to begin the kind competitive devaluation of your currency via printing press (Zimbabwe). Indeed, repetitive devaluation of currencies in an effort to make your export sector more competitive was one of the most pernicious forms of economic nationalism during the inter-war years. Countries essentially used the printing press to produce more and more domestic currency, undercutting its purchasing power relative to those of others, all in an effort to boost export earnings; get foreigners to buy your stuff while making their products more expensive for your citizens. Economists refer to this kind of policy-making as "beggar-thy-neighbor" since it counter-productively attempts to make your economy more vibrant at the expense of your neighbor (see political cartoon from Pravda, 1933).

The entire postwar European integration project-- indeed the rationale behind Bretton Woods as well-- has been designed to prevent the onset of "beggar-thy-neighbor" economic nationalism and its descent into political nationalism and war. Some in Europe are genuinely alarmed by the damage a "Grexit" might portend for the European project and a possible return to the kind of economic nationalism that destroyed Europe twice in the 20th Century. Among the many things the Greek debt crisis has exposed are some nasty political cleavages within Europe that harken back to a darker era.

The point of all this is that reintroducing the drachma would require the kind of economic discipline on the part of Greeks similar to that they are experiencing under austerity. To reintroduce their own currency and reacquire monetary sovereignty means also reestablishing the kind of credibility with markets that Greece currently lacks; it's not something you just switch back on. Floating a new drachma would entail a much devalued Greek currency relative to the Euro; something that would clearly make parts of the Greek economy more competitive. However, "devaluation" implies the overt manipulation of one's currency; a pernicious form of economic nationalism we would be wise to avoid.

No comments:

Post a Comment